The story of the twelve spies in Parashat Shlach raises a puzzling question: How can the same reality be interpreted so differently? Modern psychology offers insights into this ancient tale of trust, fear, and the power of perspective

According to biblical accounts in the Book of Numbers, Moses commissioned twelve tribal leaders to conduct a forty-day reconnaissance of Canaan. I often feel sympathy for these spies, who ostensibly just did their job. God instructs Moses to scout the land, and Moses sends them with clear instructions:

“Go up there into the Negev and on into the hill country, and see what kind of country it is. Are the people who dwell in it strong or weak, few or many? Is the country in which they dwell good or bad? Are the towns they live in open or fortified? Is the soil rich or poor? Is it wooded or not?” (Numbers 13:17-20)

The land does indeed flow with milk and honey

The scouts are to examine the land itself – whether it is good and whether there is food there; and they are to examine the community dwelling in the land – whether it is strong and fortified. After forty days, they return from the mission and report that the land “does indeed flow with milk and honey” (ibid, 26), but the peoples dwelling in it are strong and fortified. Caleb, son of Jephunneh, silences them and says: “Let us by all means go up, and we shall gain possession of it, for we shall surely overcome it” (ibid, 30), but his companions disagree with him.

Following these words, a crisis develops among the Israelites – people begin to weep, morale drops, and some of them say to each other: “Let us appoint a head, and let us return to Egypt” (Numbers 14:4). At this stage Joshua ben Nun, who was also among those who scouted out the land, intervenes and sides with Caleb, but to no avail.

Seemingly, there is a legitimate disagreement here – each spy expressed his honest opinion based on what he saw, which is exactly why they were sent. So, what was the great sin? God’s words to Moses reveal the answer: "How long will this people spurn Me, and how long will they have no faith in Me despite all the signs that I have performed in their midst?" (ibid, 11). This

was the final straw. After repeated expressions of faithlessness, God wanted to destroy the entire people, but Moses convinced Him to forgive. "I pardon, as you have asked" (ibid, 20), God says, abandoning the idea of a plague. Instead, He imposes a terrible punishment: the spies die (except Joshua and Caleb), and the people wander the wilderness for forty years – one year for each day of scouting. Why? Because they did not trust Him.

You cannot enter the country without trust, since you cannot go to war without trust. This was true thousands of years ago, and it is still true today. For a nation to win a war, there needs to be at least basic trust between different parts of the people, and between the people and the political and professional leadership. This is one of the most difficult challenges facing Israel today – waging war with what appears to be extremely fragile trust.

What makes us trust someone?

Professor Ruth Mayo, a social cognitive researcher at Hebrew University, defines trust as a state where someone feels vulnerable and places their security in the hands of another person with the thought that they will do what is best for them. But trust isn’t just about deep psychological factors – it can be surprisingly superficial. Research shows we instinctively judge faces as trustworthy or untrustworthy, even though facial features have no actual connection to trustworthiness. When people view “trustworthy” versus “untrustworthy” faces, they respond differently to the same questions. The key insight: we think differently in a state of trust and in a state of distrust. Mayo’s crucial finding is that when we distrust, our default response is to seek alternatives.

The sin of distrust

And this is the secret of the story of the spies. The ten spies who brought the evil report and Joshua and Caleb saw the same reality, except that the ten were in a state of distrust, like most of the Israelites. This is why people immediately thought of an alternative: "Let us appoint a head, and let us return to Egypt" (Numbers 14:4). Joshua and Caleb were from the outset in a state of trust – and therefore said there was nothing to worry about. Our initial measure of trust will cause us to interpret situations completely differently. The great sin of the children of Israel and the ten spies was their fundamental state of distrust toward God and Moses.

Trust can cause us to interpret reality in ways that create dangerous conceptions; distrust can make us rebel and seek alternatives even when they’re much worse. Both are problematic biases. The right thing is to neutralize these instinctive biases and decide in each case what measure of trust to give based on reality and data.

The story of the spies remains remarkably relevant today. In our own lives, we constantly face moments where we must choose between trust and skepticism, between moving forward despite uncertainty or retreating to familiar ground. The challenge isn’t to blindly trust or perpetually doubt, but to recognize when our default settings are clouding our judgment – and to have the wisdom to see clearly through both fear and faith.

On behalf of the Beit Avi Chai team and in my own name, I wish us safe days and may we know how to trust each other in the right measure at this time.

Lior Tal Sadeh is an educator, writer, and author of “What Is Above, What Is Below” (Carmel, 2022). He hosts the daily “Source of Inspiration” podcast, produced by Beit Avi Chai.

For more insights into Parashat Shlach, listen to “Source of Inspiration”

Translation of most Hebrew texts sourced from Sefaria.org

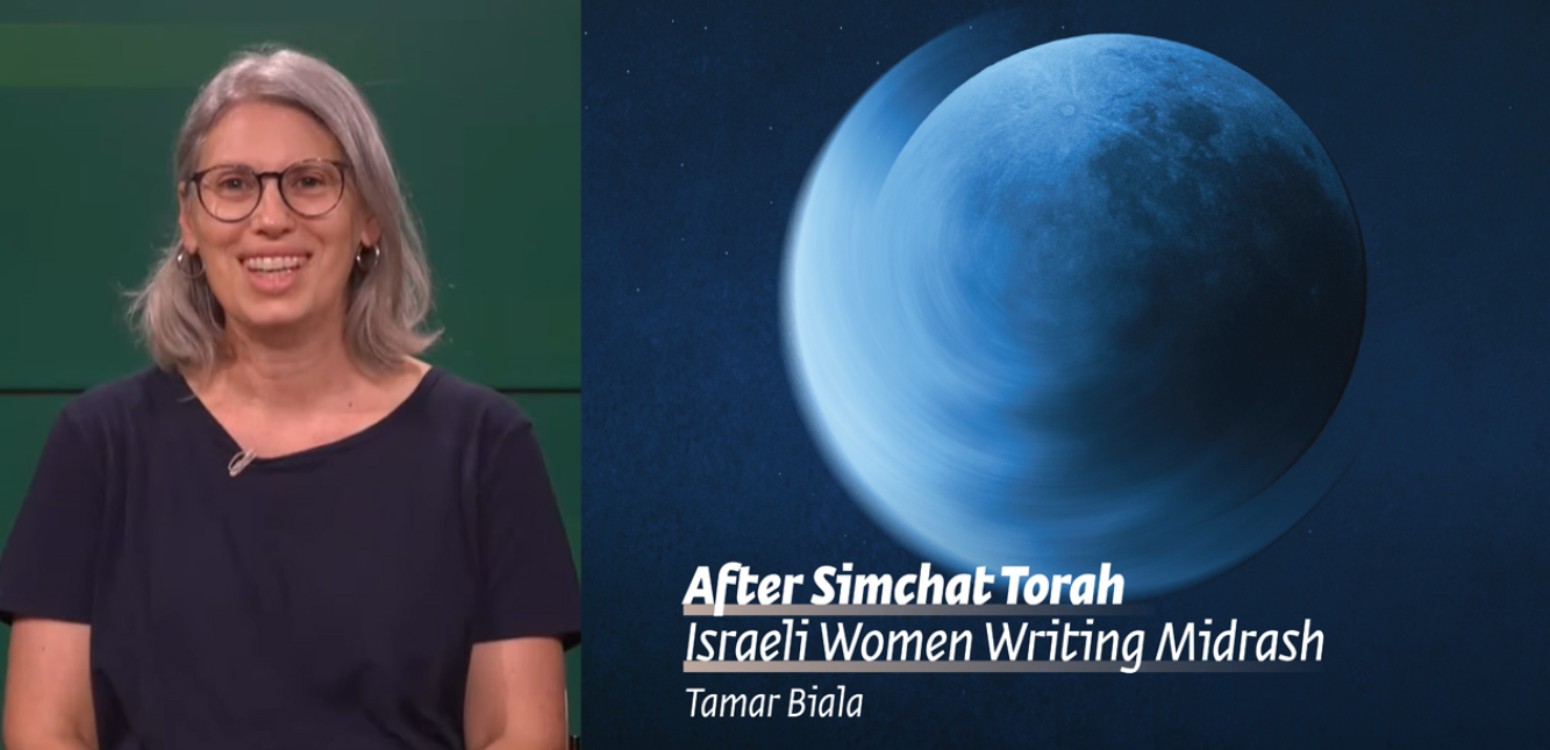

Main Photo: created using AI

Also at Beit Avi Chai